House History

The history of Owston Hall estate can be traced back to 1086 and the Norman Conquest of William the Conqueror. The estate is mentioned in the Domesday Book and, throughout its history, has been owned by numerous landed gentries.

Although the current house can be traced to at least the 1700s, it was built on the site of a much earlier house or settlement. By 1775 it was owned by a widow, Mary Cooke, who went on to acquire land from the Duke of Ancaster, making the complete estate over 1000-acres large. Since then, the changing manor ownership and the exploration for coal for 100 years from the 1860s, has shrunk the estate to the current, more manageable, 147 acres that hotel guests can explore.

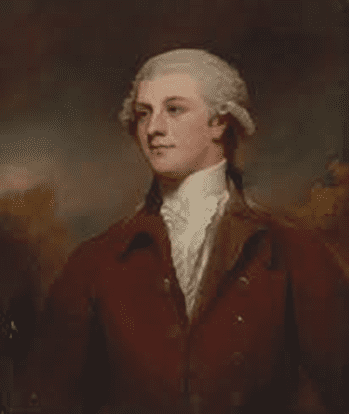

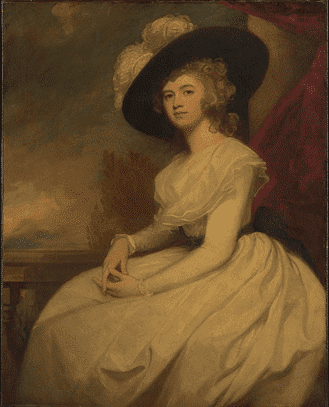

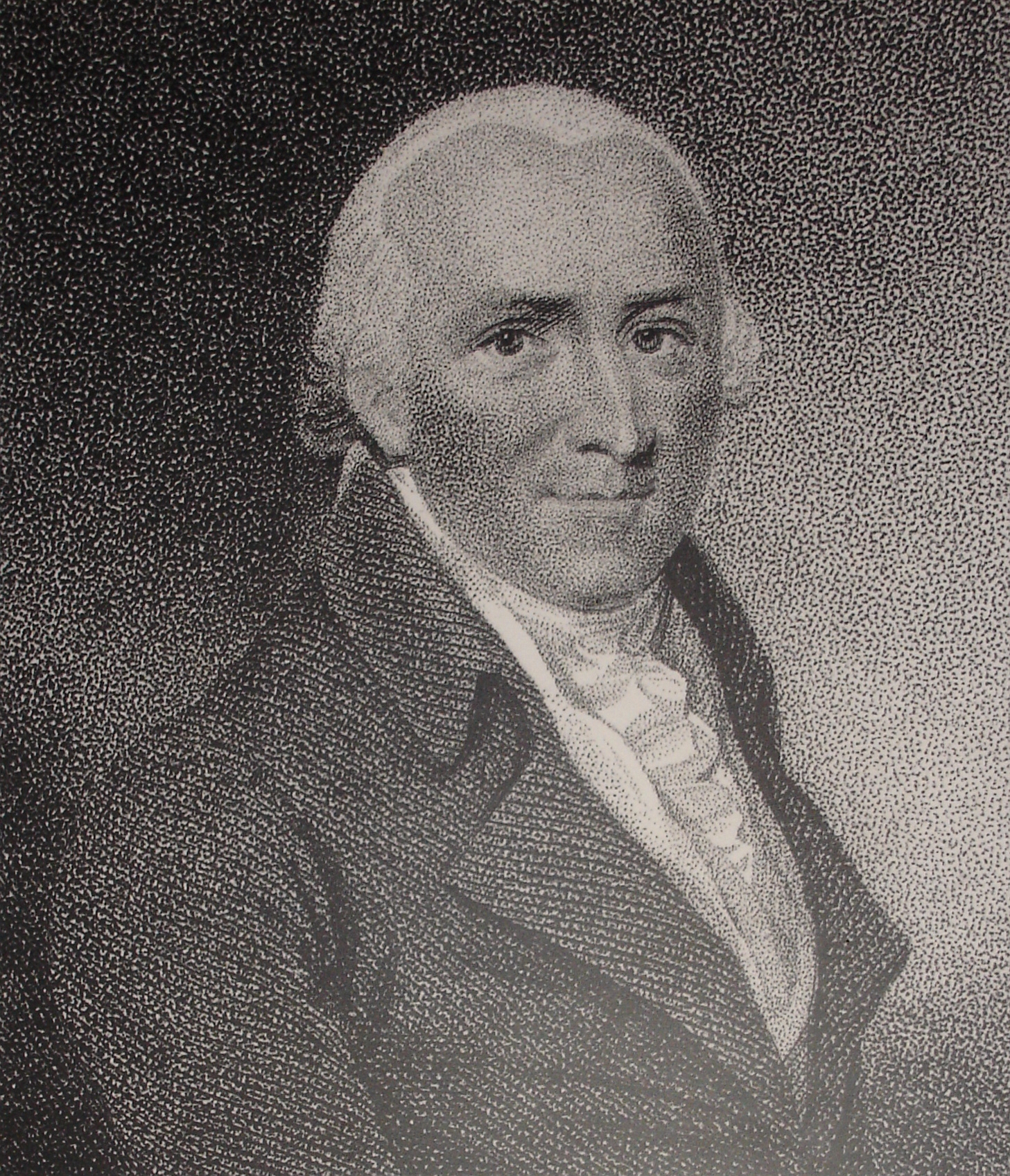

The Neoclassical architecture of the 18th century hall reflects the popular style of the time wonderfully: grand scale rooms, simple geometric forms, and Greek/Roman detailing. In 1785, Mary Cooke was succeeded by her son Bryan Cooke and his wife Frances (pictured) as lord and lady of the manor. In 1793 Bryan invited eminent landscape gardener Humphry Repton (pictured) to create plans for the Owston Hall parkland. Elements of Repton’s famous Red Book designs and plantations are still incorporated into the layouts that you see today.

Bryan Cooke

Frances Cooke (nee Puleston)

Humphry Repton

In the 1800s, the manor house underwent substantial architectural alterations, and then again in the early 20th century when the front section was turned into flats.

By the early 1930s, the hall had been converted to a golf club house with most of the parkland turned into a golf course. Large parts of the estate were sold off to cover death duties in 1946 and the remainder, including the hall and former parkland, were sold in 1979 – its owner kept the golf course and turned the hall into a hotel, as it remains to this day.

In 2022, the Martin family from Doncaster, purchase the estate after seeing the potential to return it to its former glory. Understanding the significance of the hall’s heritage and Grade II* Listing, the Martin family is dedicated to restoring the manor sympathetically whilst creating a world-class hotel, golf and spa resort for the benefit of guests and the local Doncaster community.

The Full History By Tim Cooper

- Topography of Owston Estate, Doncaster

The estate straddles a small ridge in the magnesian limestone area of South Yorkshire, within the flood-plain of the River Don. The ridge runs almost centrally through the layout of the existing estate, its high point being the feature known as Windmill Hill. The land to the east of the ridge is particularly low-lying and has, until quite recently, been liable to regular winter flooding.

In terms of the communications network, the estate is situated close to the stretch of the old Great North Riad (generally followed by the line of the modern A1) between Doncaster and Pontefract and is accessed from the main road between Doncaster and Selby.

- The Medieval Manor of Owston

The manor appears in Domesday Book (1086) as ‘Austun’ suggesting a meaning of ‘Eastern Settlement’, presumably in relation to the older-established vill of Burghwallis and its satellites of Norton and Sutton in the adjacent area.

Prior to the [Norman] Conquest, the estate had been held by three Anglo-Saxon land-holders, Gluniairnn, Ulfketill and Skotakoll and comprised four carucates of land with the potential for supporting three plough-teams. The three pre-conquest tenants were replaced by one Alfred who held the estate from Ilbert de Lacy – one of William the Conqueror’s tenants-in-chief who had been granted large tracts of the West Riding, which constituted the Honour of Pontefract. Alfred’s holding consisted of one carucate of land (about 100-120 acres) held in demesne (i.e. cultivated for his own use), and his tenantry of twelve villeins (villagers) and five bordars (smallholders) who between them held four carucates, eight acres of meadow and a tract of woodland measuring ½ league long and ½ wide. The value of the estate before the Conquest had been assessed at 60s. but in 1086 it was worth 20s. less, probably reflecting the Conquerors deliberate ravaging of the Yorkshire countryside following the rebellions of the 1070s.

No church is mentioned in Domesday and the Anglo-Saxon estate would probably have been part of an extended parish based on Burghwallis whose church includes extensive remains of late-Saxon or early-Norman masonry. The surviving herring-bone masonry in the fabric of Owston church, analogous to the local examples of Malty, Marr and Brodsworth, suggests that it was probably built within fifty years of the Conquest and its close proximity to the present hall makes it likely that it was established by one of the early Norman lords next to his manor house, an arrangement particularly common in this area of strong, consolidated lordship (Hey, 1979: 83, 86).

The history of the estate between the early Norman period and the later Middle Ages is obscure, but by the late 13th century it was in the hands of Humphrey de Veilley who in turn passed it on to William de Hamilton, by the terms of a charter of 1295. Within forty years of this transfer the manor had devolved into the hands of the Crown, probably due to forfeiture, and by the end of the 14th century, through its grant by Edward III to his son, John of Gaunt, had become part of the estates of the Duchy of Lancaster (Hunter, 1828: 478).

In 1396 the duke granted the advowson of the church to the Premonstratensian canons of Welbeck, (Notts.), and in 1418 the Archbishop of York, Henry Bowet, instituted the church as a perpetual vicarage and decreed that the incumbent should be provided with a manse consisting of a hall, chamber, kitchen and stable with an adjoining garden or close, all of which was to be provided by the canons of Welbeck in their capacity as appropriators of the greater tithe (Hunter, 1828: 478). It is possible that a fragment of 15th-century glass depicting a clerk in monastic habit, which survives in one of the windows of the south aisle of the church, is an indication of the church’s dependence on Welbeck Abbey.

Various incised grave slabs, dating from the 13th and early 14th centuries and now built into the fabric of the church, are probably to be associated with lords of the manor. Three chantries were established in the church, the latest being that in honour of the Virgin Mary which appears to have been built by Robert Hatfield in memory of his wife who had died at the turn of the 15th century. The pair are commemorated by a fine incised brass now located at the western end of the nave. The terms of the chantry foundations appear to have included the support of a schoolmaster; a number of sources suggest the existence of a thriving school at Owston by the end of the Middle Ages (Hey, 1979: 95; Hunter, 1828: 481; Hey, 1986: 116-117).

From a population at the time of Domesday Book of under twenty households, Owston developed into an important manorial settlement. Tax returns of 1343 record the names of fifty heads of freeholding families, and ninety individuals were assessed for the poll tax of 1379 including a dozen who were of sufficient means to be liable for above the standard rate. However, Owston appears to have shared the fate of a great number of English villages which suffered drastic population decline in the later Middle Ages, for a variety of reasons ranging from the effects of the Black Death to the deliberate clearing of peasants from the lands of lords wanting to turn their estates into deer-parks.

By the turn of the 16th century the village was dominated by a single yeoman farming family, the Adams-es, with only a few smaller freeholders surviving in their shadow (Hey, 1979: 127).

- The Owston Estate from the 17th to the 19th Centuries

By the end of the 16th century the Adams-es had held the manor on lease from the Duchy of Lancaster for several years and, during the reign of James I, they were granted full possession by the Crown. However, their tenure was to last for less than a century. Apparently due to the financial extravagance of the last two Adams squires of Owston, the family were forced to sell the property in the last years of the 17th century, and the estate records show that part of the purchase agreement was the settling of debts by the new owners. The beneficiary was Henry Cooke, second son of Sir Henry Cooke. of Wheatley. The Cookes had enjoyed a long association with the Doncaster area, with two members of the family serving as mayors of the town in the late 16th and early 17th centuries (Hunter, 1828: 478-9; Usher, 1964: 177).

Following the death of Henry Cooke in 1717, the property passed to his son, Anthony, whose most important legacy to the estate was the acquisition of a Parliamentary Act of Enclosure in 1760. The Act secured the enclosure of about 400 acres of common land including Stockbridge Common, Owston Common and Tilts hills. A number of cottages, farms, tenements and pastures were affected, and it also involved the laying-out of some new roads and bridges. There was evidently some dispute with the tenantry over the loss of common rights. A commission was instituted to hear grievances and it was noted that ‘several persons claim shares of the said intended enclosure alleging that they are possessed of antient mesteads [sic] whereon antient messages stood but have been pulled down upward of twenty years and no right of common [has been] claimed during all that time.’ The final settlement and apportionment involved Cooke in a certain amount of recompense to those tenants concerned but his cause was aided by the fact that one of the commissions was his father-in-law, Anthony Eyre (Doncaster Archives DD.DC E 1/1).

Anthony Cooke’s death in 1763 left his widow Mary concerned with the business of consolidating the estate in preparation for its succession by her young son, Bryan. Her first task, in 1788, was to commission a survey of the property which estimated that it comprised a total of 949 acres, which included the accretions made by the enclosure of eight years previously. Mrs. Cooke then embarked on a process of land acquisition to increase her son’s inheritance. At around the same time as she commissioned the survey she was involved in the purchase of property worth £22,000 at Adwick-le-Street and in 1775 she acquired the greater part of the lands of the Duke of Ancaster at Thorpe, amounting to over 1,000 acres, for £16,000 (Usher, 1964: 184)

Following his succession as lord of the manor in 1785, and marriage in the following year, Bryan Cooke’s main interests were in the redevelopment of the house and its immediate grounds in line with current fashions among the county gentry. According to Usher, Cooke had commissioned the architect William Lindley to draw up plans for the modernisation of the house in 1786, with the majority of the work being carried out between 1794 and 1795 under his direction. In the first year, building costs amounted to £818 10s. 3½d. and it was probably due to the increasing cost incurred that the plans were changed; the front elevation was to have been set off by elaborate colonnades, but this scheme was abandoned in favour of a plainer frontage involving ionic pilasters. Lindley’s final bill for the alterations came to £3,000. Pevsner, and subsequent authorities, have ascribed the refashioning of the house to William Porden; at present the reason for this difference in interpretation is not known (Usher, 1964: 191; Pevsner, 1974, 389; Magilton, 1977, 62).

The remodelling of the hall in the currently fashionable neo-classical style was to be accompanied by the landscaping of the grounds. To this end the landscape architect Humphry Repton was invited to visit Owston in the summer of 1793 and in the following year he presented his proposals for improvement in the form of one of his customary ‘Red Books’, a number of which survive from estates around the country. The effects of his proposals were shown by water-colour illustrations which included overlays depicting the various prospects of the estate before and after improvement. Well-known for his castigation of the ideas of Lancelot “Capability’ Brown, the leading practitioner of landscape gardening of the previous generation, Repton was not unduly flattering about the scene he met at Owston: ‘No situation in the grounds at Ouston can boast any very striking features or extensive prospects; but the verdure is good, the soil dry, there are many good trees (tho’ mostly in rows), yet with proper management these rows may be broken and grouped into less formal lines.’ (Usher, 1964; 191-2; Doncaster Museum; ‘The Red Book of Owston’) Available to purchase (PDF) at New Arcadian Press

Curiously, Repton’s roughly surveyed plan of the estate included the provision of a ‘new house’ on a site to the west, though the accompanying text indicates that no part of the house seems to justify any addition to it (Illus: Plan for landscaping of estate from Repton’s ‘Red Book’). Work was, of course, proceeding concurrently on the house on its present site. The main features of Repton’s plans were the creation of a number of wooded plantations to improve the view across the grounds of the estate, and the creation of a small pool to provide greater diversity in the landscape. He stressed that his overall plan, at Owston as elsewhere, was for the creation of a park, in his view the proper setting for the house of a country squire. Of the view from the house to the west he comments: “This is certainly the most extensive of any view at Ouston, but I cannot think it the most desirable; a vast range over flat cornfields to distant high ground…is not the kind of scenery that long delights us in the view from a house; as I before observed, we expect park scenery [underlined] appropriated to the mansion.’ The impression of a country park was to be emphasised by new sweeping approach roads which were to avoid the existing village, or else its houses were to be tidied up, so as not to spoil the outlook. Less than satisfied with the unimpressive view of the estate which was to be had from the approach road from the north, he suggested that it should be lined with trees to hide the shabby buildings’. (Doncaster Museup: “The Red Book of Owston’

As with the remodelling of the house, it was almost certainly the scale of costs involved which deterred Bryan Cooke from carrying out in detail Repton’s plans for the landscaping of the grounds. An idea of the costs involved can be gained from the surviving accounts relating to Repton’s work, along similar lines, at Corsham Court (Wills.). These show that the scheme, which included the provision of some 6,000 trees, amounted to £2,110. Faced with similar costs on his estate of Attingham Park (Shrops.) in the 1790s, Lord Berwick adopted Repton’s proposals on a limited basis (Bettey, 1993: 90, 92).

The death of Bryan Cooke in 1821 marked a change in the landed interests of the family. His marriage to the heiress of the estate of Gwysaney, near Mold in North Wales, meant that his son, Philip Davies-Cooke, inherited a joint concern. One of his first actions as new squire of Owston was to go some way towards realising his father’s plans for the landscaping of Owston and it appears that a scaled-down version of Repton’s plans were carried out by him in the 1820s. The lithe plan of 1842 shows the demesne area largely emparked, with some of the tree plantations perhaps owing their siting to Repton. The walled kitchen garden (as it appears in Repton’s plans) was evidently a feature of the later 18th century. Davies-Cooke spent a great deal of money on his Yorkshire estate, primarily in modernising tenants’ houses and farm buildings (Usher, 1964: 206-212; Doncaster Archives: DZ.MD/88).[Illus: Tithe award map, 1842-3]

Having remedied some of the deficiencies in the grounds, he turned his attention to the house, the front elevation of which he regarded as unfashionably plain. In 1827 he employed an architect to redesign this part of the house incorporating a remodelled portico supported on pillars, a flight of steps to the entrance and an ornamental balustrade. Yet, once again, a squire of Owston had over-reached himself and the plans were abandoned. Instead, they were realised on a smaller scale in the construction of Doncaster Lodge, at the main park entrance, to an ornamented neo-classical design (Usher, 1964: 206-212).

Within a generation of the creation of the joint estate, the Davies-Cooke family were to abandon their immediate interests in Owston. The next squire, Philip Bryan Davies-Cooke had suffered from chronic chest ailments since childhood and was advised to move away from the damp climate of Yorkshire by the family physician in 1881. In addition, adverse weather had periodically affected his income from the property. In 1866, for instance, the Great May Flood, as it became known in the area, left much of the estate under water for a long period resulting in rent arrears of over £1,300. After a few years spent in Dorset, the family finally settled in Gwysaney in 1888 (Usher, 1964: 228).

- The Estate in the Twentieth Century

Perhaps the most significant change in the nature of the Owston estate came with the opening of the Doncaster coal field in the 1860s. Encouraged by reports from the mining companies and in the local press, P.B. Davies-Cooke decided to investigate the possibility of coal mining on his land. Initial trial shafts were unpromising; the ‘Owston No. 2 Bore Hole’ cost £167 and showed that at a depth of 262 feet there was very hard limestone but no coal. However, on his succession to the estate in 1903 Philip Tatton Davies-Cooke was determined to investigate the possibilities further and new borings revealed the presence of workable coal seams under Owston Park. The major obstacle was the liability of the area to flooding, which was apparently circumvented by the use of a new German method of refrigerating the top of the shaft area.

Bullcroft colliery was sunk in 1908 and was in full production two years later. In 1913 the colliery company leased the mineral rights to the family and, from this point to the nationalisation of the industry in 1947, the mining royalties constituted a major part of the estate income. It was also from this time that Owston took on the quality of a rural island in the midst of an industrial area, which it still evokes despite the recent closure of the majority of the working pits of the Doncaster coal field. At the peak of production in 1929, Bullcroft colliery employed 2,600 men and there were still over 1,000 working there in the early 1960s. The income generated by the mining activity initially allowed the family to pay off its debts and undertake maintenance and improvement of the estate (Usher, 1964: 235).

However, this reversal in the family’s fortunes was to be short-lived. The death of Philip Tatton Davies-Cooke in 1946 incurred substantial death duties which required that large parts of the Owston and Gwysaney estates be sold off. At Owston, the sale of large tracts of low-lying farmland meant that the estate was reduced from its 19th-century extent of over 3,000 acres to under 1,000. The house, too, had undergone changes since the family left in the late 1880s. From 1883 to 1889 the hall and grounds were let and between 1910 and 1914 the house was completely vacant. In 1914 the front portion was let, which in 1928 became the club house of a newly opened golf course. In 1940 the hall was requisitioned by the army until the end of the war when it was converted into a number of self-contained flats, one of which was retained for the use of the family during their occasional visits to Owston (Usher, 1964: 247-50).

In 1964, when Philip Ralph Davies-Cooke commissioned the writing of a family history, the estate consisted of the house and its associated outbuildings, five farms and eighty acres of woodland among the total of just under 1,000 acres. The walled garden was by this time being used as a commercial market garden and the grounds were being cut for hay. In 1951 the stables had been let to a local Mainer (Usher, 1964: 254). The garden area around the house was re-landscaped when the late Colonel and Mrs. Cooke returned from Gwysaney to take up residence at Owston upon their retirement in 1969; a survey of the grounds undertaken at around this time revealed that the soil was not very deep since the limestone belt lay just below the surface, and the landscaping involved the import of large quantities of top-soil from the surrounding area (Doncaster Archives: DD.DC/E7/1-19).

The death of Colonel Davies-Cooke in 1976 once again left the family facing sizeable death duties, which on this occasion necessitated the sale of the remaining parts of the estate. The property was purchased in September 1979, by Mr. Peter Edwards. A Mrs.

Kathleen Davies-Cooke retained the lease of the family’s flat in the hall for about two years at which time she returned to take up residence in North Wales (P. Edwards, pers. Comm.).

- Conclusions

Owston Estate has enjoyed a long history from the pre-Conquest era to the present day and obviously constitutes an important part of the historical landscape of the Doncaster region.

The overall shape of the main park area of the estate, being of a roughly circular lay-out amidst an otherwise mainly linear field-system, suggests the possible survival of the boundaries of the original medieval demesne [land] of the lord of the manor. This possibility is reinforced by the survival of the local name ‘Owston Demesne’. Although as yet no direct evidence has been found, it is possible that in the later Middle Ages this area could have been converted to use as a deer-park, a common practice among landlords during this period and one which would serve to fossilise the original outline of the manorial unit in the landscape.

The architecture of the church would suggest a fairy early Norman seigneurial foundation which, in most cases were built close to the manor house. It is probable, but not necessarily the case, that the later hall was built upon the foundations of the original manor complex. Associated with the church was a vicarage with associated buildings and agricultural land which would almost certainly have been situated to the east of the church in an enclosure which survived until the recent past with the field name ‘vicar ing’, suggesting an enclosed area appended to the vicarage. Early OS maps mark a building in this area as a vicarage. In the later Middle Ages the church also supported a chantry school, one of about ten in the South Yorkshire region.

By the fourteenth century Owston had become an important settlement in the area, although it was to experience population decline in the later Middle Ages. It is uncertain where the main focus of this settlement would have been located. Magilton suggested the most likely area was that between the church and the present hall, although this area is currently in use as a car-park and yields no obvious physical evidence. The settlement area was most likely to have been located at some point between the car-park area and the edge of the present field boundaries to the north of the estate, though the possibility cannot be discounted that there was an original location on some other spot within the demesne area. It might be significant in this regard that the Enclosure Commission. of 1760 revealed that some houses had been pulled down on the estate in the mid-18th century. Analogous examples, however, would suggest somewhere in the immediate vicinity of the church and the present hall as most likely.

Although the present outline of the estate forms a coherent feature in the general landscape of the area, the exact details of its landscaping in the modern period are uncertain. Landscape evidence and the estate financial records point to the conclusion that the suggestions of Humphry Repton, made in the late 18th century, were not carried out, though a partial landscaping on similar lines was undertaken in the 1820s which included the plantation of groups of trees. The last significant alterations were made to the immediate vicinity of the house during the 1970s and modem ploughing has obviously modified the appearance of the present estate.

Bibliography Doncaster Archives:

DZ.MD/88: Owston tithe plan and award, 1842-43 DZ.MD/160/58 : Notes on Owston Hall

PR.OW: Owston township parish council records DD.DC: Owston estate records

DD.DC/A/1 : Owston manorial records

DD.DC/E/1/1: Owston enclosure records, 1760-1771 DD.DC/E3/1: Owston field surveys and valuation records DD.DC/E4/1: Owston maps and plans

DD.DC/E5/1 : Owston rental books

DD.DC/E7/1-19: Owston woods, gardens and parks records DD.DC/E10/1: Owston particulars of sale, 1795

DD.DC/N/1 : Owston Parliamentary Enclosure records DD.DC/0/1: The church and living of Owston

DD.DC/0/2: Owston tithe books, 1775-1776

DD.DC/0/3/9: Owston tithe rent charge books, 19thC

DD.DC/0/3/42: Owston township records, rale book and poor rate assessment

Doncaster Museum:

Humphry Repton’s ‘Red Book’ for Owston, 1792-3

Secondary sources:

Bettey, J.H., (1993) Estates and the English Countryside. London

Hey, D., (1979) The making of South Yorkshire. Ashbourne Hey, D., (1986) Yorkshire from A.D. 1000. London

Usher, G.A., (1964) Gwysaney and Owston. Privately published.

Pevsner, N., (1974) The Buildings of England; Yorkshire, West Riding, 2nd edn. London Magilton, J.R., (1977) The Doncaster district:a n archaeological survey. Doncaster

Golf course proposals in historic landscapes: an English Heritage Statement. London

Hunter, J,. (1828) A history of the deanery of Doncaster, vol. 2. London

Brooks R.H., Davies-Cooke, DR. ,. Gagg, D., All Saints Owston: guide to the church. Privately published.